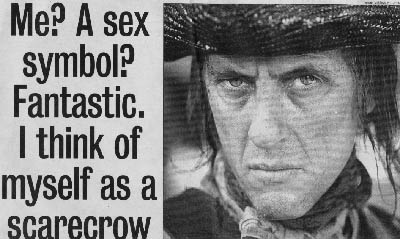

Me, A Sex Symbol? Fantastic. I Think Of Myself As A Scarecrow

Sunday Express – 22nd October 2000

By James Rampton

We are in what only can be described as the back of beyond in the Czech Republic, and Richard E. Grant is taking a break before a big scene in the Scarlet Pimpernel, BBC’s lavish new costume drama. In front of 300-odd rowdy peasants, the dashing Pimpernel is about to perform a typical deed of derring-do. Disguised as a disheveled rosette-seller, he will spring on to a horse and cart hitched to a guillotine and pull the dreaded apparatus to the ground.

As Grant takes a sip from his restorative cup of tea, his sleeve slips down to reveal not one but two glinting modern wristwatches. The actor insists on wearing an extra watch permanently set at the time in his native Swaziland. It is the gesture of a man whose every act cries out: “I’m different – and don’t you forget it.”

This desire to be different is a significant part of his allure as an actor. Grant has always cultivated the image of a man apart, a misunderstood, often angry figure at odds with the world. That tag has stuck since he first came to Britain from Swaziland in the early Eighties and secured his breakthrough role as Withnail, the archetypal outsider in Withnail And I, Bruce Robinson’s cult film about two alienated actors who go on the bender to end all benders in the Lake District.

“The first thing that made an impression was Withnail.” Grant reflects, before taking another mouthful of tea. “If I had played a terror-stricken Kafkaesque man whose sister was Steve Martin and who sat silently in the corner of a room, I would have had a different career. But because Withnail was so off his head and extreme, I got streamlined for a while into playing that type of role.”

However much he protests, the fact remains that Grant has few equals when it comes to playing unhinged. Think of his collection of characters on or – more often – over the edge: the demonic ad man in How To Get Ahead In Advertising, the grieving husband suffering a breakdown in Jack And Sarah, or his scarily convincing paedophile in Trial And Retribution. To those, he can now ass the over-the-top figure of Sir Percy Blakeney (aka The Scarlet Pimpernel), a man so confident he leads a double life straight out of a comic book.

These sort of on-the-margins roles have helped Grant become something of a sex symbol. Women are eager to find out more about this charismatic yet mysterious maverick with the blowtorch-bright eyes and the wiry, tortured-artist’s frame. But, happily married to voice coach Joan Washington and with a young daughter, he laughs at the very idea. “Me, a sex symbol? How fantastic. I think of myself as a scarecrow, so how other people see me is a peculiar revelation. Perhaps if I looked like Harrison Ford, I would be besieged, but as I don’t, I’m not.”

Being an outsider has also turned Grant into that rarest of beasts: an actor prepared to ignore luvvie gush and speak plainly about his industry. How many other performers would you hear describing one of their big films – in this case the big-budget Bruce Willis vehicle, Hudson Hawk – as “a great, self-basting turkey. I watched it with my hands in front of my face. I hated it.”

Similarly, Grant’s acclaimed and deliciously indiscreet diary, With Nails, has hardly made him flavour of the month within the terminally paranoid and self-regarding Hollywood community. In one section, he is wonderfully catty about Jodie Foster: “[She] lasers me with the compliment that she has just taken four sets of people to see Withnail And I. Oh, sweet, waffle-syrup thank-you Jodie. My brain is bleating to try and act casual, but body parts have curled up to their toes.”

But he has no regrets about the candour of his bestseller. “Put it this way, I wasn’t sued by anybody and I’ve not been barred from working. It was never my intention to do myself out of work, but rather to write as honestly as I dared about the process of what filming actually involves.”

“Things can go well or go haywire – there’s built-in human drama there. I’m giving an insider’s view of a world where you already know the characters, but don’t know exactly what they do.”

“When you read Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton’s diary. It’s very immediate. It’s not been edited or filtered through the mists of history. That’s why I love the diary form. You get it direct, untrammelled.”

All the same, the 18 months he spent in Hollywood left Grant with a pretty jaundiced attitude towards the place. “While you’re working in L.A. it’s a fantastically supportive community. But the moment you’re not it’s like you’ve suddenly got leprosy. Bully for those who can stay sane in those circumstances in L.A. My wife said that after a year there, I was starting to come up with an alarming amount of psychobabble. Current affairs in L.A. is who’s sleeping with who, not what’s happening in Bosnia.”

“In Hollywood, you’re also defined by what you look like. If I pumped iron and spoke with an Austrian accent, maybe I too could do Terminator 5, but it’s not something I have sleepless nights worrying about.”

Close friends with Steve Martin – they email each other every day – Grant has had a ringside view of the corrosive nature of fame. “I was around Julia Roberts at the time of Hook. She just got chased around. We were due to meet for dinner and the venue was changed five times. To have that kind of hounded life must do something to you. It must make you wary of anything anybody says to you.

“How can you not have an ambiguous attitude to the whole idea of celebrity? You’re in and out of favour at such incredible speed. How can you buy any of the stuff you read or people tell you?”

He goes on to recount a story in bitter detail. “I met one agent 16 times – that sounds very numerically anal – and every time I met her, I had to reintroduce myself. The day Withnail And I came out, she called me and I had this wonderful revenge of being able to say, “I’m sorry, have we met? I have no recollection. What do you look like?” Once you’ve had any experience like that, the whole thing seems so arbitrary.”

Grant is currently happy to be out of the limelight and working on his directorial debut, an autobiographical film about growing up in colonial Swaziland during the Sixties. It is called Wah-Wah, which is how others thought the upper-class Brits spoke in those days.

A mischievous, delightfully frank presence, the 42-year-old is a refreshing antidote to your average self-important “Aren’t I wonderful?” actor. He is as likely to tell a story against himself as anyone else.

He reckons he owes his level-headedness to that greatest of British characteristics: taking the mick: “Living in London keeps your head and feet and heart and soul on the ground. There is this great British sensibility of self-depreciation and not being allowed to take yourself too seriously. When you fail, so many people make a joke of it to your face – ‘Thank God you’re not being too successful’. It’s fantastically healthy for your state of mind.”

Richard E. Grant may not be the most sought after house-guest in Hollywood, but he’s welcome here any time.

The Scarlet Pimpernel continues on Wednesday, BBC1, 8.30pm