Mother’s Mischief

The Sunday Times – Sunday 16th October, 2005

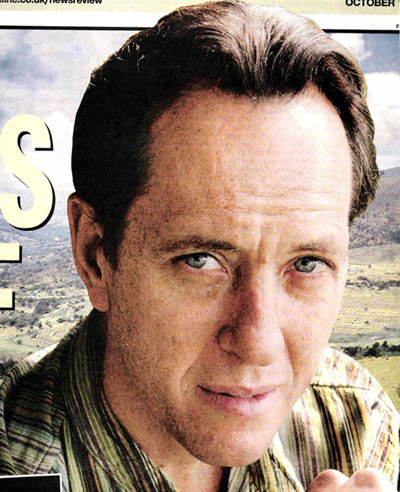

Richard E Grant remembers a family scandal that blighted his African childhood and explains to Jasper Gerard why he has gone back to his homeland to turn his painful past into a film.

“My father tried to shoot me but missed because he was so drunk,” says Richard E Grant. “He was furious I had tipped away a crate of his whisky.”

Today the actor is not coming over as the suave, slightly snakey gent who has starred in many movies and briefly held Hollywood enthralled. He is looking like a student on a gap year: battered flared jeans, collarless shirt and beads, all infused with a spooky youthfulness.

This is not coincidental. At 48 the star of Withnail and I and How to Get Ahead in Advertising has spent a year in the African bush, finding himself. He realised he had to quit Hollywood when his wife told him: “Your idea of current affairs now revolves around Arnold Schwarzenegger’s private life.”

So he went off to make a film about Richard E Grant. Or rather, about his White Mischief childhood under the fading light of empire in Swaziland, the landlocked British colony nestling within South Africa’s craggy bosom.

“It was that last gasp of colonialism,” he intones crisply when we meet in the foyer of a Surrey hotel. “People being overtaken by history.”

It was actually a bit more personal than that: at the very moment that Swaziland was gaining its independence, Grant’s mother Leonie declared unilateral independence from her family.

“I have kept a diary since I witnessed my mother’s adultery at the age of 11,” confides the actor.

It Was 1968, the summer of love, but in the farflung colonial outpost in which Grant lived as a boy it felt more like the roaring twenties.

Both his parents were South African. Leonie was of German descent while her husband Hendrik was an Afrikaner. He had spent most of his life in Swaziland, rising to the post of director of education for the British colonial secretariat, and he respected the colony’s African heritage.

“My father made it clear we were guests in an African country,” says Grant.

With independence approaching, Swaziland’s small white community was gripped by a wave of hedonistic debauchery that undermined its pretence at prim parasol-and-petticoat gentility.

“There was a sense we were all there for a finite time. That infused all the English with a kind of hysteria, a feeling of being displaced that led to a hothouse atmosphere… Too much leisure, too much drink and too little responsibility.”

For Grant’s father, relief lay in the bottle; for his mother, in sex.

Mama was driven to gasps of ecstasy on the family car’s front seat by her husband’s best friend John. All the while she assumed Richard was asleep in the back. But as ever Richard was watching, listening.

“It was a poisonous secret for a child to have to keep,” he says quietly. “I was gobsmacked. The diary was all I could confide in, and I have kept one ever since.”

The burden of his secret was lifted in the worst way when Leonie told her husband that she was divorcing him after 13 years of marriage. But the earth had not moved simply for mama; the divorce was an earthquake for the expat community.

“It was fine to shag around as long as you didn’t divorce,” Grant says with palpable bitterness. “My mother’s big mistake was divorcing; that’s what caused the scandal. Half the children I was at school with had parents involved with other parents.”

In an imaginative twist, Leonie suggested that her cuckolded husband marry the now dumped wife of his former best friend and that they divide Richard and his brother Stuart between them. Hendrik furiously rejected this solution.

Richard’s parents.

With gossip raging more quickly than a bush fire, Leonie fled for South Africa while her lover absconded to Peru. Richard and his brother remained with their abandoned papa in Mbabane, the Swazi capital.

“I recognise as an adult that to live with someone you no longer love is unworkable, but at the time it was devastating,” says Grant.

The Grants tore themselves apart amid much comfort. “We lived in a standard-issue government house with standard issue government furniture, and after independence we moved into a substantial house with swimming pool and servants. It was benignly feudal, like a 19th-century novel. We were fed, watered and waited on.”

The twists continued. Straight after his mother bolted Grant was dispatched to boarding school in Natal, and the first time he returned home he was introduced to his new stepmother. His father had remarried to “a former air hostess he had only known for six weeks”.

Grant’s brother adapted, but the sensitive future actor pined for his mother: “I played with my puppet theatre as a way out of it all.”

He also loved his father but was forced to witness Hendrik’s decline into chronic violent alcoholism caused by the pain of the divorce. Grant saw him transform into a “schizoid addict”. “By day he was charming and provocative; by night he was a different person.”

Was alcohol an excuse for the violent rages, or the cause? “No one chooses to be an addict,” says Grant sharply. “He died aged 52. He never recovered from the divorce.”

All this is retold in Grant’s film, which is called Wah-Wah after the sound of drunken waffle being spoken by sozzled expats on the Mbabane country club veranda.

In the film, Grant has recreated and included the homicidal reaction when he poured all his father’s booze away in an attempt to curb the old man’s drinking.

“My father, when very drunk, pointed a revolver at my forehead at close range, fired a shot – but obviously missed.”

Grant sighs: “An everyday tale of colonial life.”

With material that dramatic, it took him just two-and-a-half months to dash off the script. The film stars Gabriel Byrne as Grant’s dad, Miranda Richardson as mama the bolter and the incomparable Julie Walters.

While gaining rave advance reviews after previews at the recent Edinburgh and Toronto film festivals, Wah-Wah has been criticised for depicting black people as smiley wallpaper. Grant says the critics miss the point, for that is precisely how natives were seen by the colonialists.

“If you sent a few Englishmen to Igloo land they would create a class system,” expounds Grant. “You can see on holiday it is established in a hotel in a nanosecond. And it is the source of so much British comedy.” (Despite his Afrikaans heritage, his humour is unmistakably English.)

Wah-Wah has also been criticised by his brother. But there is a history here. The last time the brothers met was at their father’s funeral back in 1981. Brother Stuart subsequently ripped into Brother Richard, claiming the rising star tipped up at the funeral with orange hair and theatrical self-obsession.

Brother Richard has taken a pensmith’s revenge by writing Brother Stuart out of the film, portraying himself as an only child.

The dynamics of the feud are impenetrable, but if the charge is that the actor was insufficiently scythed by his father’s death, have a look at his wrists: he wears two watches, his own and – set to Swaziland time – his father’s. And he never goes near booze.

By contrast the film led to a reunion with his mother, now 77, frail but still very much alive in South Africa. When Grant first conceived the film project a decade back he wrote to her. This elicited an 18-page reply, and she is due to attend the premier in the new year.

“It was a great rapprochement which was profound,” Grant says softly. “It would have been extremely difficult to make the film without her approval but she read the script and agreed. The film is not a lash-fest, or revenge; it attempts to make sense of what happened. As an adult you can feel compassion and forgiveness.”

Did he not feel she should have taken him and Stuart? “She was not to know what leaving would do to my father. She thought it was for the best; she was so consumed by scandal.”

Grant still feels damaged. “If you look at all the most monstrous dictators of the 20th century you do not need to be a genius psychologist to realise their childhoods had a deep effect. I am not saying that a bad childhood necessarily turns you into a psychopath, but the hurt is there. Hitler was all too human.”

As things turned out, his salvation came at his boarding school in South Africa. It was liberal and multiracial, and he got to act with one of Nelson Mandela’s daughters, a fellow pupil. By the time his father died Grant had begun a stage career.

The struggling actor who came to Britain in his early twenties found the mother country “manicured” and “shockingly full of people… three suburbs of London had a higher population than Swaziland”.

But it also reminded him of home. Indeed he portrays Swaziland in Wah-Wah as more British than bingo. “It was England transported,” Grant says. “Equatorial Ealing.” Its mountainous landscape resembles a “sub-tropical Wales”.

He professes a love for the “light, sounds and smells” of his homeland. So imbued was he with this love of his birthplace as a young thesp that he would burst into Swaziland’s national anthem when asked to sing at auditions.

Despite annual trips back home, the shooting of Wah-Wah was Grant’s first extended stint there for more than two decades. The King of Swaziland gave permission for him to make the country’s first film since independence.

“It was pretty well access all areas,” Grant says. “People I knew from childhood were extras. And real people involved in the plot are shown in the film. In the best sense of amateur, people’s willingness to help was boundless.”

Swaziland, he says, “had not been infected with the greed and all that ‘I have my rights’… ‘how much can I get?’… when a film crew normally rolls into town”.

Still, a lack of infrastructure made filming tricky: “The amount of hoops, wheels and fire you had to leap and climb over and under made it a case of, ‘If you knew then what you know now, would you have done it?'”

He adds: “It has been the most extraordinary odyssey, a backstage story that I could not have made up… The shenanigans in the producing side are ear-shrivelling, tongue-bleaching experiences.”

So he is not overly keen to work with certain people again? “You could say that,” he smiles. “I am sure it is quite mutual: but a crook is a crook is a crook, Gertrude.”

Richard in 1962.

Still, he learnt fast: “Ridley Scott said you have to make your mind up, even if you change it five minutes later. Otherwise it will fall apart very quickly; I have been on films where that has happened.”

The experience has far from put him off directing. “Oh no, not remotely,” he says. “It is the most satisfying thing as opposed to being an actor for hire. I even loved being asked the 3,000 questions a day down to whether these are the right biscuits. For a detail obsessive it is the perfect job.”

When Richard E Grant first came to London he lacked the essential “E” in his name. Gossip columnists see it as affected, though he insists it was because Equity already had another Richard Grant. It’s not quite that simple, however. The E stands for Esterhuysen, his real surname.

He was unemployed at the time, “the perfect preparation to play an unemployed actor” – his role in the enduringly popular Withnail and I, the cult film that shot him to fame in 1987.

“Some tell me they have watched it 200 times; I was in Oxford the other day and a young Withnail obsessive asked if he could take my photo. I told him he could but he would have to stop his hand shaking first.”

By the 1990s he was a rising star in America. But tinseltown soon lost its twinkle. “You either shoot cartoons, or films like cartoons. I have no interest in constantly running away from very big explosions. I was in a supposed blockbuster called Hudson Hawk and it was a pile of s***.”

Such frankness is rare in a successful actor, and he is not finished. “With a film costing $75m you don’t expect it to be a turkey. But it went awol at once. When I tried to get out of it my American agent said, ‘Oh no, that would be career suicide.’ I said, ‘It can’t be more suicidal than actually appearing in it.’ He said, ‘No, the people who are making this made Die Hard’, and that was netting 300 gazillion. Your standing is made very acutely clear. I wish now I had just quit.”

He confesses: “Because you are only in one bit you delude yourself another bit will be magical or it will be marketed so cleverly people won’t realise it is a great big dog of a film.”

He also grew tired of playing English villains. “With the end of the cold war the bad guy could no longer be Russian and, with political correctness swathing through, villains can’t be ethnic minorities. English actors going back to James Mason have seemed willing to play unsympathetic characters that leading Hollywood men wouldn’t touch.

“Bruce Willis said to me he would never play somebody who was gay. I said, ‘Why not? You are an actor.’ But he was being realistic: people who have tried to break out end in disaster. Meg Ryan took her kit off in In the Cut and America did not want to see their girl next door doing that. I don’t think her career has recovered.”

He now lives by the Thames in London with his wife Joan, a voice coach, and their teenage daughter Olivia, and he is content to find himself touring provincial Britain in a play, Otherwise Engaged – despite describing an earlier theatrical run as “mind-numbingly, arse-cripplingly boring”. Otherwise Engaged moves to the Criterion Theatre in London on October 25, and Grant is happy at the prospect of the West End stage.

“I think you want to be surrounded by people with a similar sensibility. If you have been raised in a colony you do feel slightly third-eyed when you arrive in Britain, but all my cultural references are from here.” After a recent stretch filming in the outer reaches of the Czech Republic “you just long to see a sign for M&S”.

He does not feel out of it being back here. “Not at all; when you are out of work (in Los Angeles) it is like wearing a sign saying ‘I am a leper’. I remember going there to do background research for a novel I wrote called By Design. I kept being asked, ‘Why are you wasting your time writing that? Why aren’t you writing a movie?'”

He describes Hollywood as “fear-filled”.

“You only need to be there when the sun is not shining to notice the grim determination and the need to be on every billboard. Every meeting has some agenda. People smile in case you might be of use 10 years down the line. If you are successful everyone is your friend. God forbid that you are in a movie that’s a clunker.”

A dreary trait of actors is their tendency to gush about the great privilege it was to work with each other. Refreshingly, Grant is not that polite.

“When I see actors talking about world peace, it makes my sphincter weak,” he declares loudly, prompting guests in our hotel foyer to splutter on their morning coffee.

“There is a difference between Emma Thompson talking about a world catastrophe and – God! – Demi Moore talking about it. Goldie Hawn talking about the elephants has a different impact than Joanna Lumley. Sometimes it doesn’t seem a million miles from a Miss World contest. I just don’t have strong enough mental furniture to withstand it.”

Yet before one is too taken by this high mindedness, remember that Grant appeared recently in a telly shocker called Celebrity Shark Bait, where famous sorts were lowered in a glass cage to confront some rather large white gnashers. How does that fit with his hunger for “creative fulfilment”?

He shoots the sideways guilty look that has become his trademark.

“We were not told what it was going to be called,” he offers. “They said they would fly us first class and I knew Ruby (Wax) would be there, who is a good laugh. And I have always been obsessed with sharks. I did not realise we were going to be pitted against each other and that they would try to get us to slag each other off like Big Brother.”

If the intention was to show the leading man reduced to a cry baby, it backfired. “They couldn’t get me out of the water. You were so close it was amazing: seeing those sharks come towards you really got your jubblies going, I can tell you.”

And he emits a rather filthy laugh, suggesting that old White Mischief is not entirely dead.