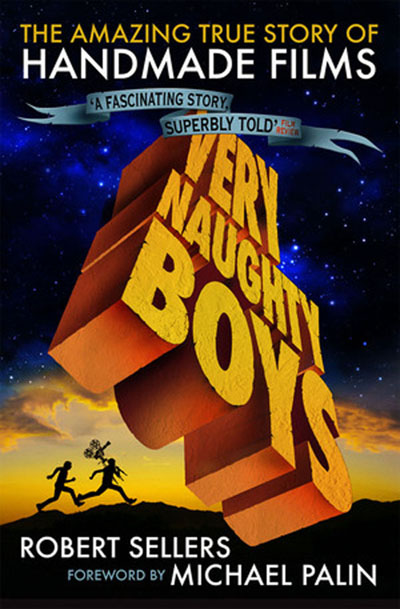

Very Naughty Boys: The Amazing True Story Of HandMade Films!

TwitchFilm.com – 19th September, 2013

Below is an excerpt from Very Naughty Boys: The Amazing True Story Of HandMade Films! This excerpt focusses on the making of ‘Withnail & I’ in 1986. As you’d expect there are a few hefty swear words so please take note.

Todd Brown, Founder and Editor

Back around 1978 or so the Monty Python lads were hard at work setting up what would be their second (and best, in my opinion) proper feature film, The Life Of Brian. But they had a problem. They’re backer had fallen out and the entire project was in danger of coming apart at the scenes. Salvation came in the form of long time fan and former Beatle, George Harrison, who created HandMade Films to see Brian through to completion and in the process launched one of the most successful and iconic British production companies of all time, at least for a time. And now the whole story of what happened is hitting book shelves with Robert Sellers’ Very Naughty Boys: The Amazing True Story Of HandMade Films.

It all started when Beatle George Harrison stepped in to fund Life of Brian when Monty Python’s original backers pulled out. His company, HandMade films, went on to make some of the best British films of the 80s (Withnail and I, Time Bandits and Mona Lisa among them), but then things started to go wrong…

Granted exclusive interviews by the people who made it happen, including Alan Bennett, John Cleese, Robbie Coltrane, Sean Connery, Terry Gilliam, Richard E Grant, Richard Griffiths, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, Neil Jordan, Paul McGann and Michael Palin, author Robert Sellers reveals behind-the-scenes stories as intriguing, diverse and occasionally surreal as HandMade Film’s output and puts its outstanding contribution to cinema in its rightful place.

This is the incredible and often hilarious insiders’ story of what happened…

The book hits shelves September 24th and we’ve got an excerpt for you below. Read on!

————————————————–

Paul McGann had only just completed the controversial BBC drama serial The Monocled Mutineer when his agent rang with another offer of work. ‘Darling,’ oozed the voice, ‘there’s a script about Whistler.’

‘What?’ McGann said.?

‘It’s called Whistler and Me or something.’?

‘What, the painter?’ asked McGann.?

‘Presumably. Anyway, it’s winging its way to you now so give it a look.’ McGann put the phone down. A film about Whistler? Not inconceivable, there’d been a rash of period movies recently. ‘So I thought, well, all right, because I look quite good in a frock. I look quite good in period things. And it was a movie and I hadn’t done a movie. And it arrived. And the first time I read it was on the tube. I was in hysterics and that’s never happened before or since. People were trying to look over my shoulder at what I was reading because I was almost crying reading this thing.’ The script, of course, was for Withnail and I.

The audition for Withnail and I was at a house in Notting Hill Gate rented by an American producer called Paul Heller. Inside, the director, Bruce Robinson, sat scruffily dressed in leather jacket, jeans and with a cigarette dangling James Dean- like from his mouth, his hand never far from a can of lager. McGann tried to act cool as he sat down and the director asked, ‘What part do you feel you could do?’

?That was easy. ‘Marwood,’ said McGann, guessing Robinson was testing him out. ‘I’d really fuck that Withnail part up. I couldn’t do that.’

Robinson nodded. ‘Well, I’m glad you said that, because I saw you as the other one, too.’

McGann recalls, ‘I was so nervous, because you want to make an impression, you want to get it right. And I walked in and I can’t remember getting my coat off. I can’t even remember sitting down. And Bruce said to me, “You’ve got the job.” And I was struck dumb. I wanted to just burst.’

Robinson had more or less cast McGann already as the ‘I’ character (referred to as Marwood in the script but unnamed in the film), having seen him perform previously. Now he was merely curious to observe him in the flesh. After all, McGann was effectively going to be playing Bruce Robinson himself. The role is semi-autobiographical, it’s Bruce 20 years ago, and the director wanted to make sure he’d got the right guy.

Because first choice Daniel Day-Lewis had turned down an offer to play Withnail, preferring to make The Unbearable Lightness of Being instead, McGann was asked if he might come in and read scenes with prospective Withnails, a character Robinson has described as an ‘awful, fucked-up, quasi-homo bounder; this vituperative, nasty, acid git’. He agreed and over the next two days sat in this swanky house as actors — some famous, some less so — paraded in to read extracts from the script, specifically two scenes, the one in the kitchen with the untouched washing-up and the pair’s haunting goodbye on the park bench in Regent’s Park.

One of the actors McGann instantly recognised, as both hailed from the same drama school — Kenneth Branagh. Robinson did actually toy with the idea of casting Branagh as Marwood but he insisted on trying out for Withnail, despite his obvious unsuitability. Robinson saw Withnail as Byronic and emaciated, whereas Branagh, ‘looked like a partially cooked doughnut’. Not very Withnail. McGann remembers, ‘But Branagh’s so confident. He came in and he was confident. He barged in and he took over. But the guy I thought would get the job, who was completely out there, was Eddie Tenpole Tudor. Eddie was Withnail. He’s even a fucking Tudor, for God’s sake! He’s a toff, the guy was twenty- eighth in line to the throne of England or something. This is Withnail. He was completely right, as far as I could see, and he did a fantastic reading.

‘There were these two American guys, friends of Paul Heller, who’d come over. They looked like the Thompson Twins from the Tintin books, and they were sitting side by side on this sofa watching us. And me and Eddie are reading this scene on the park bench. And in the film, Withnail gobs on the floor. So we’re doing this thing and Eddie gets some gob from the base of his spine somewhere and he actually really gobs and it goes “Thwack” and this thing lands on the turn-up on one of these guy’s trousers. And I can see the veins in Bruce’s neck and he’s gone the colour of a Marlborough packet trying to contain this laughter.’

McGann was convinced Tudor would land the job, even after a certain Richard E Grant walked in. Grant had been sent the script by casting director Mary Selway and was desperate to play it, though didn’t believe anyone would be stupid enough to actually give it to him. Robinson didn’t even want to see him, looking aghast at his photograph in Spotlight when Mary Selway showed him it. ‘I’m looking for Byron, not a fucking fat, young Dirk Bogarde,’ he said. Grant had never been to a film audition before. ‘I remember Richard coming in and I actually didn’t think he was much good,’ McGann recalls. ‘He was very, very nervous. And I remember Bruce saying later over a cup of tea something like, “What did you think of the South African?” I said, “I dunno.” Bruce said, “There’s something about him. I’m going to get him back in.” So Richard came back and he was ready for it this time. And it was Withnail, stood in front of you. He had it. It was spot on. And good for Bruce, he got him back in. But then the cunt sacked me.’

The first McGann heard about his dismissal was when his agent called. ‘I’m really sorry, Paul, it’s not going to work out, the Withnail thing.’ He couldn’t believe it, having already been offered the role, though no contract had been signed, Robinson was now letting him go. And, worse, he hadn’t had the guts to do it face to face. McGann admits, ‘I remember feeling justifiably really fucked off about it. I’d been sitting there with all these actors, some of whom didn’t know what they were doing, and my function as I saw it was just to be there and try and give them as much as I could. God knows what I was doing. I must have been just hamming it like mad and Bruce had sat there having kittens about what I was doing, panicked and turned me down. I said to my agent, “I’m not going to take this. He’s wrong. Get me an audition. Get me back in, I can’t let this guy get away with this. He’s nuts.” So I had to go back in on the Monday to audition for the job I’d been given on the Thursday. Extraordinary.’

By this time, Richard E Grant was firmly ensconced in the Withnail role, with Robinson’s words of ‘Granty, we’re gonna make a fucking masterpiece’ ringing in his ears. But McGann still had to pass the test all over again. ‘So I auditioned again and sat with Richard who’d got the job. The boot now was on the other foot. How about that? Bruce tries not to remember that now. I’ve talked to him about it since. He said, “Did I really do that?” I said, “Yeah, you bastard.” So we had to go through this embarrassing rigmarole of sitting there again and I got to the end of the audition and I looked at Bruce and there was this silence and he said, “Oh, all right then. You’ve got the job.”‘

Like McGann, the first time Grant read the script of Withnail and I it had a profound impact on him, perhaps more so. ‘Never before or since have I read something that conveys what goes on in my head so accurately,’ he later wrote. One of the reasons why the film works so brilliantly and has endured for so long is that the script was ready. Robinson began it back in 1970 and it couldn’t be bettered, it had been in his head fermenting and maturing for 15 years. McGann observes, ‘That script went on to the screen unchanged. Not a single line was altered. It’s completely unique. Our camera operator said, “I’ve never known this and you’ll never see this again.”‘

At a special charity showing of the film in 2000, organised by Richard E Grant to raise funds for his old school in Swaziland, Robinson decided to auction his original manuscript dating from 1970. And there it was, typed on his old Remington, with handwritten notes in the margin, some of it absolutely verbatim, word for word scenes from the film. It was that ready. The script sold for £7,000. The buyer was Four Weddings and a Funeral writer Richard Curtis.

Everyone thought Robinson was mad to sell the script and, after the event, he grabbed hold of Ralph Brown, the actor he’d cast in Withnail as Danny, the drug king, to tell him, ‘Richard Curtis has bought my screenplay.’

Brown replied, ‘Has he?’ Then, after a short pause, jokingly suggested, ‘Why don’t we go outside and meet him in the foyer and just do him and nick it back?’

A few days later, when Robinson got home to his farm in Herefordshire, there on his doormat was the script. Curtis had returned it. Bruce called McGann to tell him that Curtis’s gesture had been one of the nicest things anyone had ever done for him.

The story of Withnail and I is loosely based on Robinson’s own experiences as a perpetually skint drama student living with a bunch of mates in diseased digs in Camden Town during the Sixties. As the decade wore on, his friends either married or got jobs until there was only Robinson and this other guy, a self-destructively hard-drinking wannabe actor called Vivian MacKerrell, left in the house. Highly educated, MacKerrell became something of a cultural mentor to Robinson, spouting at length about Keats and Baudelaire in between the prodigious consumption of alcohol. Eventually, he went, too, leaving Robinson alone with practically no money, hardly any food, a solitary light bulb and a mattress on the floor. It was the winter of 1969 and Robinson was unemployed and in utter despair. Returning one day to the empty flat, he found himself weeping uncontrollably and praying to the God of Equity for a job, anything, even a coffee commercial. Tears soon turned to laughter at the absurdity of his situation and he decided to write about his predicament and the friend who’d left him behind.

It started life as a novel, mutating later into a screenplay collecting dust on the shelf until 1986 when Paul Heller, whom Robinson knew from his screenwriting jaunts in LA, read it, loved it and recruited David Wimbury, whose close association with HandMade was instrumental in getting them involved. ‘You’ve got to make this movie,’ Wimbury insisted to O’Brien. ‘This is a film you can’t afford not to make.’

Certainly, it’s hard to imagine any other company other than HandMade taking on such a unique film as Withnail. McGann says, ‘At the time, it was only HandMade, I guess, whose house style was funky enough to touch it. For both its punters and performers, HandMade was the funky alternative. I remember the associated kudos of working for them. It must have been like recording for Stiff Records in 1978. It had that cachet.’

But not everyone at HandMade was so like-minded. Before he resigned, John Kelleher saw a copy of the script and wasn’t keen at all. ‘I thought it was the most horrible thing I’d ever read. I remember it coming in. I think Ray Cooper must have given me the script. Bruce Robinson was hanging around HandMade a lot then because he was part of a group that included Ray and George. Ray said, “We’re thinking of doing this. What do you think, commercially?” The trouble with the Withnail script was it was very hard to get past the beginning in this rat-infested kitchen in Camden Town that Bruce described in incredible detail. And you just couldn’t help being completely turned off by that. It was very hard to get past it.’

Prior to filming, Robinson organised a week’s rehearsal for the cast in a vast wood-panelled drawing room in an old house on the grounds of Shepperton Studios. McGann remembers, ‘It was owned or used by The Who. It was a big open space. In the corner was a kitchen area and a fridge full of booze. And we’d work office hours. We’d arrive at nine and go home at five.’

While at Shepperton, the supporting roles were cast. As the poacher the lads meet on their disastrous holiday break in the Lake District, Michael Elphick, then a big TV star as Boon, agreed to appear as a favour to Bruce, as they’d been at drama school together. They couldn’t afford his rates. ‘But he did it for a few quid and a bottle of scotch,’ Robinson noted. Richard Griffiths, a HandMade stalwart, agreed to play Uncle Monty, a character Robinson had conjured up as being representational of all the people who’d harassed him as a drama student, those ‘artistic gents who were after my bum’.

One important audition was for the part of the drug-dealer Danny, and someone who found himself up for the part was a little-known actor called Ralph Brown. ‘They’d been trying to cast this part for months without success. I hadn’t done any films at that point, so I wasn’t exactly on top of their list of contenders. I think Mary Selway had seen me on stage and got me an audition with Bruce. I remember I sat in a nearby park for about an hour going over my lines before I went in.’

Brown arrived for the audition totally in character, bare-foot with painted black fingernails, long wig, eye shadow and shades. ‘I looked a bit strange.’ It blew everyone away and Robinson all but gave him the part there and then. Modelled partly on someone who worked at a record shop near London’s Central Drama School, who sidelined in selling dope, Brown was given near carte blanche to create his own Danny, basing him on people that he’d grown up with in Lewes in East Sussex. ‘Lewes was the kind of place where punk kind of arrived in 1982… it was still very much a hippie backwater… cider drinking and smoking joints. There were various characters around the town, one used to be in and out of prison for various nefarious activities including drug-dealing, others were in bands. I was only 13 or 14 and these people were really larger than life for me and they were slightly glamorous. One guy called Noddy used to attempt to roll the longest joint ever known to mankind and he had this stoned, serious take on life where he’d tell you something in very serious tones that was absolute bollocks. So I definitely understood Danny in that sense.’

As rehearsals progressed, Grant and McGann grew more familiar with the script and Robinson’s intentions. Earlier, they’d had trouble with some of the lines. Aware they were meant to be funny, both tried too hard to make them funny, telegraphing the jokes almost. Robinson was so opposed to that, repeatedly stressing that the comedy would come from the characters and situations. McGann recalls, ‘Bruce said to us, “There are no punchlines. Boys, get it out of your head now, there are no gags. This film will work because we’ll play it for real. You’ve got to play it for real.”‘

Then the bombshell dropped — Grant didn’t drink, he was allergic to the stuff. This was news to Robinson; he hadn’t thought to ask, ‘Oh, by the way, Richard, you do drink, don’t you?’ Taking McGann to one side, a panic-stricken Robinson blurted out, ‘He doesn’t drink. He doesn’t drink.’ Then turning to Grant, ‘There’s nothing worse in films than a bad drunk act. We’re dead.’ And Grant was sitting there, forlorn, saying, ‘I know… I know… I’m so sorry.’

Some quick thinking was called for. It was Robinson who came up with the idea that Grant should have a ‘chemical memory’ of what it was like to be completely poleaxed. He approached the fridge in the corner of the rehearsal room. ‘There were beers and coolers and these airplane miniatures,’ McGann says. ‘I remember it was an airplane miniature of vodka. Bang in a glass. Doused. And he drank it. What a sport. And Bruce is saying, “Richard, we’ve got drivers, if you don’t feel well we’ll call it off and take you home.” And I thought, Bollocks, I’m having a beer. And it was incredible, Richard went through every single stage of being pissed, literally from that lovely moment when you have that first drink and you get that first mellow feeling, and then incrementally the stakes get raised and you get a bit merry, and then you have another one and you start gibbering and flirting and then you start knocking into things. Grant did that, visibly. But it happened in minutes, maybe 20 minutes, to the point where if the police see you they have to have a word with you. I fucking swear this happened.’

Robinson was quick to exploit the situation and got them reading and rehearsing scenes, any scenes with drink in them or scenes under the influence. McGann remembers, ‘We were sitting together and an arm went round my shoulder and Richard looked at me and said, “You’re such a fantastic actor.” It’s like the pub drunk going, “I love you, man.” And he said to Bruce, “Thank you so much.” And Bruce is going to him, “Do the scene, just do the scene.” And I have to say he was great, the things he was doing were great and he was laughing and enjoying himself. And then he started making these noises, involuntary sort of whoops. And then these, like, Navaho sounds. It was absolutely hysterical. Then he stopped whooping and went green and looked for a window and threw up. It was awful, really. They got him out into a car and took him home. His wife was on the phone. “What do you think you’re doing? What have you done to my boy?” And Bruce is wiping tears from his eyes. It was so naughty. As Richard’s leaving, I swear Robinson’s going to him, “Remember. Remember!”‘

And the amazing thing is, it did pay off, the chemical memory Robinson was after worked. McGann confirms, ‘He did remember, look at the film, he remembered. It’s the best drunk performance I’ve ever seen. There’s a scene when we’re in the car leaving London and he’s leaning out of the window shouting “Scrubbers” to some schoolgirls. Look at his eyes, that’s acting. How the fuck do you do that? I worked with this guy and, even to this day, I have to marvel at what he did. And he doesn’t drink. He got on it, whatever it was, he got on it. At one point, he looks straight at me and you look at him and you go, “Fucking hell, you are out there, you are miles away.” Remember this is 9.30 on a Sunday morning. Who won the Oscar that year? Nobody was that good. Absolutely magnificent.’?

McGann also recalls during shooting how first thing in the morning he’d hear, through the adjoining doors of their hotel rooms, Grant physically psyching himself up to get into character, little wafts of smoke coming under the door from the herbal cigarettes he used instead of tobacco.

The morning after the drinking binge, Grant woke up with a demon of a hangover and foul-smelling dribble on his clothes. As he later wrote, ‘My stomach is on fire. Tongue stapled to the roof of my mouth, throat scorched and head housing an orchestra of pneumatic drills playing Beethoven’s Ninth. All for art?’ When he finally managed to grope his way downstairs, Robinson had left a message on the answer phone. ‘Granty. You did it. Breakthrough. Gonna make a fucking masterpiece, boy.’

On 1 August 1986, Grant and McGann met at Liverpool Street Station to catch the train up to the Lake District where much of the film was shot amid the picturesque countryside around Penrith. The first scene in the can was the boys’ arrival at an abandoned cottage in the middle of a howling night. McGann recalls, ‘Both Richard and I had never done a film and Bruce had never directed a picture, so we tended to spend a lot of time just staring at each other going, “What do we do now? And, can we do this? Can we get away with this?”‘ Sensing that this was their big chance, Grant and McGann really got stuck in and made the most of it. ‘They were both well up to speed,’ Griffiths says. ‘They were like baby sharks, the two of them, and I was just holding my end up, as it were. Richard had landed this part, God knows how because he had not a clue about how to present himself, and it’s probably one of the greatest performances he’ll ever give in his life. And it was all because Bruce was so generous about letting him express himself. And McGann was funny. He was constantly trailing shots. In other words, there’d be two of them in the shot doing the lines and then they’d exit and Grant would just crash out of the door and McGann would leave his face sort of vaguely looking over the top of the camera, and then go. He was getting himself a close-up. And the cameraman would look up at Bruce who knew what was wrong and kept telling McGann to stop trailing his face. “If you get out of the shot, just get out. Don’t stand there looking beautiful and then get out, just get the fuck out.”‘

On that very first day of shooting, Bruce Robinson did something quite unique. He assembled the entire crew together inside the cottage, stood on a chair and was man enough to confess that he’d never directed a film before, but that he knew what he wanted, it was all in his head, it was just from a technical standpoint he’d not the first clue and asked everyone that if they saw him make a mistake on the floor not to be afraid to pipe up. It was one of those ‘we’re all in it together’ type speeches, very Henry V at Agincourt, and the crew responded.

Griffiths’ view was that ‘Bruce was truly amazing. He would go into a set-up in a scene, he’d look at it and we’d all stand around and he’d say, “I haven’t got a fucking clue about how to do this. Anybody any ideas?” And you’d stand there in shock. Somebody was not bullshitting you. Because directors always do, they always pretend they know what they’re doing, especially when they don’t. And out would come this fountain of ideas and at the speed of light he would just flicker through them and say, “No, no, no… Ahh, that sounds good, let’s have a look at that.” And then we could rehearse it. And he said, “Yes, that’s good. Let’s shoot this way.” It was so liberating.’

Everyone knew the film was being made on a pittance, a mere £1.5 million, and that in itself created a bond of loyalty and togetherness, coupled with a sense of how special the script was. Brown recalls, ‘It was everyone’s first film — mine, Bruce’s, Paul’s and Richard’s. The crew were fairly experienced. Peter Hammond was certainly an experienced cameraman and he directed the shots pretty much because Bruce didn’t really know where to put the camera and would just say, “Pete, what shall I do with this scene?” And they’d work it out together. It was a really nice atmosphere. There was no tension, everyone was helping each other out. I think we all felt that maybe that’s the way movies were. And, of course, we’ve all made lots of films each since then and they’re not all like that. It was a lovely honeymoon, really.’