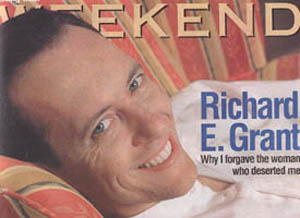

Why I Forgave The Woman Who Deserted Me

The Daily Mail, Weekend Supplement – 5th February, 2000

As a child in Swaziland, Richard E Grant was mocked over his parent’s divorce and his desire to act. But attending the school where nelson Mandela send his children taught him to overcome all this. Now, in a penetrating interview, he tells Rebecca Hardy of the bizarre and tragic events that still drive him.

Richard Esterhuysen was a rather odd, stick-thin child who played with puppets. He grew up in Swaziland in a smart house with servants overlooking the beautiful Valley of Heaven, but didn’t believe in God. Heaven and those that lived there hadn’t been kind to him. When he was just ten years old, his mother had run off to Johannesburg with a mining engineer. She’d woken him one morning to tell him she was leaving and was gone by bedtime.

He buried his pain in a fantasy world and film became his religion. The starts of the screen were his family. He yearned to be famous like them, to live in the Never-never land of happy ever afters. His father Henrik, Swaziland’s director for education, thought it was just a passing phase, like pimples. His classmates scoffed, telling him, “You’ll never make it.”

Spurred on by such taunts, revenge drove him to act. Soon, Richard had truncated his Afrikaans- sounding surname to a single letter. Then, in 1982, and shortly after his father died from cancer at the age of 51, he moved to England. He was restless, relentless, outrageous, determined in his ambition. Within five years he had become a household name, thanks to his starring role in the hugely popular cult movie Withnail and I, in which he played a desolate, drugged-up actor attempting to come to terms with the end of the sixties.

He remained angry though; angry with the mother who had left him, angry that his father should have died so young and, most of all, angry with the double standards of Swaziland’s slack white morality that allowed lazy adultery but was scandalised by divorce. The stigma of his parents’ separation was dreadful to endure as a child. Success has blunted that anger, and now, middle-age seems to have extinguished it. Richard is 42 and married to voice coach Joan Washington, with whom he has an 11 year old daughter, Olivia.

“I’m more comfortable with myself now than I’ve ever been,” he says. “When you get to your 40s you care less about what other people say about you. It’s entriely to do with age. As you get older, compassion comes hurtling through the door completely unexpectedly. It defuses revenge. I suppose you get more tolerant because you realise your own vulnerability.”

“Bearing grudges is more self-destructive than anything else. When you’re younger it’s you against the world. You think, “I’ll show them I can do this.” But after a while when you have shown them and you’re still getting employed and the bank manager isn’t burning down the front door, you can ease out of it.”

“It’s important to be able to forgive. A watershed for me was meeting the late Roddy McDowall. I interviewed him for a novel I was writing for background research. He was 70 and I wanted to find out what retired movie stars did on a day-to-day basis. He asked me how I saw myself as an old man. I’d never been asked that before. He told me the trick was not to end up bitter and twisted. He said “In this city, with the people I know, bitter and twisted is the norm.”

“Now, in my mid-40s, I see the people I meet are absolutely divided between the people who have hope and are connected to new ideas and new talent and the ones who are locked down and threatened by younger people – those that feel their sell-by date has been and gone.”

Richard doesn’t look middle-aged. His hair is cut short and gelled without a single strand of grey. He wears green combat trousers and an actor’s uniform fleece jacket. The stick thin frame is still stick-thin, but terribly youthful. His eyes are quite extraordinary; a colbalt-blue, but warm.

I meet Richard to talk about his latest project, Withnail For Waterford, a West End charity screening of the cult film attended by the original cast with an auction of Withnail memorabilia to raise money for bursaries so that children from poor families can attend his old school, Waterford Kamhlaba. He has already raised almost £50,000 from ticket sales and hopes for further donations. He has promised to respond personally to anyone who sends money. He is fuelled with enthusiasm for the project, still hugely fond of his old school. “At Waterford you were encouraged in your individualism rather than prejudiced against it. So, following theatre, music or drama was not thought of as, “What on earth are you doing?” As much as a school can form anybody, it gave me the self-confidence to go out and do something. It gave me the sense that as an individual you have the power to change your own life.”

The film industry can be a nasty, cruel business, but Richard has been heartened by the generosity he has encountered from the likes of Sir Bob Geldof, Richard Curtis, David Bowie, Lulu, Twiggy. They are friends as well, but he probably wouldn’t have known them if he’d not attended the progressive Waterford School at 14.

Founded by inspirational Englishman Michael Stern as a protest against the apartheid system in neighbouring South Africa, the emphasis was upon tolerance and humanity. Desmond Tutu and South African President thabo Mbeki sent their children there, as did an imprisoned Nelson Mandela.

“Once independence had happened in Swaziland, I was able to go to a private school. Before that it would have been seen as very wrong because of my father’s job with education in the colonial service. When I was in the government school I was teased a lot because the idea of having puppets and wanting to be an actor set me apart.”

“That’s really where the idea of revenge came from. It was particularly rough the first couple of years after my parents divcorced. I was the only kid in my year whose parents were divorced and there was a real social stigma to it. Lots of the parents had affairs, but it meant there was something wrong with you if your parents separated. “I was never beaten up but people would say, “Where’s you mum?” or “Is your mum coming back?” For a while I’d fantasise that they’d get back together. Now, the older I get the more I understand what happened. Thankfully, I’ve been reconciled with my mum over the last few years. She’s explained that she felt she had to get out. It wasn’t personal. Seeing it from an adult perspective I’ve been able to accept and forgive and take how she felt on board without bearing a grudge. I understand now that the act of leaving your partner and children is devastating on all sides. When you’re the person being left behind though, you tend to think, “I’ve been abandoned.”

“In the community I lived in there was such a pecking order as well – according to how many servants people had. We were at the top in terms of soical standing, which is why the stigma of divorce was so difficult. I was also so skinny, just like a stick insect, and I had pimples.”

Richard’s father had hoped his son would be a lawyer or a journalist. “Because I was very argumentative, he thought I should do something that allowed me to gab my way out of a situation. He knew I wasn’t going to get my fisticuffs up. I’d always talk back rather than fight.” Besides, there was no one in Swaziland who had made a career as a professional actor. The very notion was far-fetched.

“I’m just sorry he didn’t live long enough to see the kind of ongoing progress I’ve made,” he says. When Richard’s father was buried, a Swazi priest leapt down into teh grave, on top of the casket, and began to unscrew the bolts while chanting. “I’m going to raise the dead.” He saw his father’s corpse in the opened coffin. “It was insane and horrifying, but it was also funny at the same time. It was exactely the sort of idiosyncratic thing that happened in Swaziland. I remember thinking at the time, “If only he could have been here to see this.” Because, if it happened to somebody else, he would have found it terribly funny.”

“My father was an atheist. He always encouraged the notion that what is here is extraordinary and amazing, so to have an expectation that there’s something beyond it is asking a bit too much. Every morning I’d be able to look out of the window over the Valley of Heaven. It was absoluately gorgeous and he’d say, “You are not going to find somewhere else more beauitiful than this in the clouds.” Like him, I absoluately believe in the here and now. I have no expectation that there’s anything beyond. Life’s to be grabbed with every fibre of your being.”

“Life is not idyllic. There’s no such thing. There seems to be a fairytale desire for people to believe a marriage is made in heaven, that it’s perfect and you’ll live happily ever after. But the reality of life is not that straightforward. My marriage is not idyllic. I’m far too volatile and so is my wife. We argue about everything. We went to a movie the other night and had a great argument about the content of the movie and what the acting was like. We’ll argue about who is more tired than the other person or who hasn’t cooked dinner – the trival things in life.”

“Have I been temted to have an affair? I’m attracted to people on a daily basis. But have I ever had one? No. I think if you have a compatible marriage you’re not seeking it. That’s not to say you couldn’t meet someone and there’s a thunderbolt and you think, “This person has completely turned my head around. wham, bam. I’m off.” But an affair – I think if you do you get found out.”

“When I met Joan she was married and I was one of a group of ten of her students. Having a relationship with her wasn’t really something that crossed my mind. I thought she was attractive and had a beautiful voice. She was also absoluately brilliant in terms of what she did. It actually happened when I had my first private lesson with her, which concided with my discovery that she and her husband were separated. He was living in Manchester and she was in London. She was helping me with irish accents and it happened very fast. I wouldn’t have gone near her if she’d been happily married. She had a seven-year old son, Tom, and if I’d moved in on his mum and spilt his parents’ marriage up he would have hated me.”

Joan suffered three miscarriages trying to give Richard a child. They had a baby daughter, tiffany, who was born prematurely at seven months. She died the same day. It was a terrible loss; the sort that time numbs rather than heals. “I wouldn’t want what happened to us to happen to anybody,” says Richard. “But if you’ve gone through death together it reinforces your bond to that person. It isn’t something that is easily rubbed out. It just forms who you are and how you are. It’s only when you are in a crisis that you find out about yourself and those around you. You see where and who your real friends are. It’s not unrelated to fundraising for the school. People make promises and then when you actually ask: “Are you going to commit?” you very quickly sort out who is for real and who is fake.”

Richard has just finished writing a screenplay, called Wahwah, about life in Swaziland. “A disillusioned American woman once said that’s what the expats spoke, wah-wah, so it seemed ideal as a working title,” he says. He will direct the film towards the end of the year and is returning there soon to research appropriate locations. Three decades have passed since Richard Esterhuysen sought comfort in the never-never land of film when his mother deserted him. He no longer thinks like is like the movies, although movies have became his life.

“It’s been wonderful and grotesque in equal measure,” he says. “Because the cruelty is something that you’re warned about as a young actor, but as nothing compared to what it’s actually like. There are vast sums involved in making movies and the cruelty, what people do to each other to stay at the top, is dreadful. The important thing is to forgive, move on and not hold gudges.”

Donations to the bursary fund may be made to: Waterford School Trust, 13 College Lane, London NW5 1BJ.