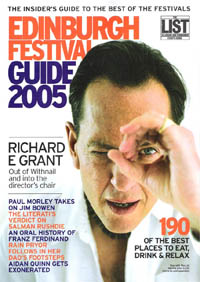

A Swazi Actor Speaks Of ‘Wah-Wah’

The Guardian Online – Thursday 11th August, 2005

Richard E. Grant has made a film about his boyhood in colonial Swaziland

By Sally Vincent

Richard E. Grant is a maverick with a plan and a new film.

“I have kept a diary,” he said, “since I witnessed my mother’s adultery at the age of nine.” As he spoke, an elderly woman was slowly trundling her luggage trolley so close to our knees we had to draw our legs out of her path. Richard E. Grant was unfazed, as though his narrative focus was so fine he had not noticed her at all.

He is a disconcerting fellow. This morning, at the crack of dawn, he came off the red-eye from Newfoundland and, if he was a normal human being, he’d be crashed out in his pit, sleeping off his jet lag, not spring-heeling around this rowdy hotel. I can never trust manic energy, let alone a man with eyes the color of turquoise. It’s not natural.

He is not, he said (not for the first or last time), a shrink. He can only tell me he began his habit of diarising at a time when he was beset by guilt and loss. He knew something terrible and he couldn’t tell anyone about it, so he wrote down his understanding of the aforementioned debacle as a way of off-loading the pressure of what he knew. And went on doing it because it became his way of dealing with the world.

“It means you are simultaneously inside and outside your own life all the time,” he said, “watching yourself experiencing what is happening to you, then having a written conversation with yourself about it. It’s a kind of control mechanism; an exploration and a way of keeping a record.”

So excruciating is his self-consciousness, he has only once watched himself on the screen and that was nearly 20 years ago when he sat through the entirety of Bruce Robinson’s glorious Withnail And I in such an agony of disillusion that by the end he was practically welded to his seat and had drawn blood from his wife’s comforting hand. There-after, he was lionized up hill and down dale, but deep down he has always known he buggered up, let everybody down, missed the boat, exposed himself as a total no-hoper who would never work again.

He also knows, and will say with perfect equanimity, that Withnail was his first big break, without which he would never have worked with Altman, Coppola and Scorsese, never been the movie star who, in the mid-1990s published a memoir of his years in Hollywood that, yes, does credit to his addiction to diary-writing despite its catchpenny title With Nails, which doesn’t mean anything except a lack of confidence in the undoubted charm and cleverness of its content. He shrugs that one off. What could he do? The publisher had to know best, after all – they thought he was worth publishing.

After 60 films, things haven’t got any better.

“You finish a movie and you think, there, you’ve done it, really well, or best you can. But if you watch it, you see it was just bollocks. You have to look at the discrepancy between what you hoped and imagined and the reality of yourself and all your shortcomings. You only see your own failure. I’d rather,” he said, “stick with the first idea – just have the experience of working – and leave it at that. You’ve got to protect the old bravado.”

It has been 10 years since Grant first thought of writing and directing his own story, and nine since he cocked the snook at Hollywood with With Nails, an acerbic account of his days in LA, for which he knew he would surely be punished. He does not expect to be invited back. “What is there now?” he said.

“Famous people running away from explosions. That’s it. They call it production values. Audiences will queue round the block to see an unimaginably highly-paid film star running away from a fantastically expensive explosion. They think it’s their money’s worth. I despair that’s what people have to do.”

It does, however, explain why so many “thesps,” as Grant insists on calling his fellow actors, move away from the obscenely big-bucks industry and into television and small production companies – “to enact being human beings instead of cartoon characters leaping from implo-ding buildings.”

Somewhere back in Grant’s paternal ancestry, there were men who were Dutch or Hungarian and certainly Afrikaner. Yet he feels his father was an Englishman, working for the British government, and he, himself, is a Swazi who happens also to be English. Now living in Surrey, south of London, a brisk walk from where we sit, he will always classify himself as an immigrant.

He used to wear two watches, one telling Greenwich Mean Time, the other the time of day in Swaziland. Swaziland was his home. Where he was born. Where he grew up and where his heart is. When called upon to sing at auditions, he would stand solemnly and belt out the Swazi national anthem. He didn’t mean to be funny.

He patently enjoys talking about his homeland. The singular beauty of its landscape, what he refers to as the serenity of the indigenous population, the nefarious eccentricities of the European ruling class.

“Swaziland is a small part of south-east Africa, the last country in the continent to gain its independence,” he said, sounding rather as one of his father’s kindly schoolmasters must have sounded as he stood by a British government-issue blackboard in front of a crowd of happy Swazi schoolkids.

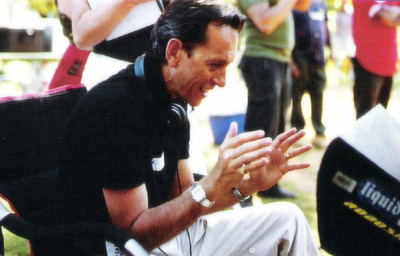

Grant got permission to film in his country, granted by the King of Swaziland, and got together a star cast (Gabriel Byrne, Julie Walters, Miranda Richardson, Emily Watson, Celia Imrie) last June. It took him seven weeks to make his movie.

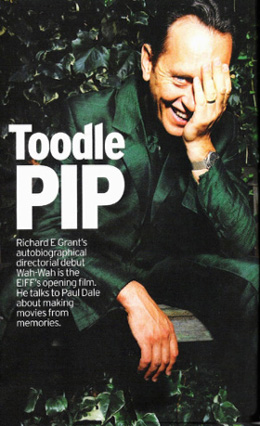

If Wah-Wah was a self-indulgence in its making, the finished product is a prime example of a genre rarely, if ever, attempted by British or American film-makers: a child’s experience, impeccably observed through the narrow lens of the child’s perspective.

We chatted on about the film for a while: how he called it Wah-Wah because that was how his dad’s second wife described the conversational tone of colonialists at their leisure; the country club’s choice of Camelot for the am-dram treat for Princess Margaret’s official visit to mark Independence Day; and how, driven by lack of white talent to include a black man in their production, they scrupulously whited-up his face with plimsoll cleaner so Margaret wouldn’t notice. Even so, she made her excuses and left in the interval. Said she wasn’t feeling well, apparently. It gradually emerged, to my astonishment, that give or take the odd tinkering with the timescale, Wah-Wah is not just true, but literally true, frame by frame.

‘Wah-Wah’ opens the Edinburgh

International Film Festival on Aug. 17.

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.

“This week’s free download, brought to you by The Times, Times Online and Audible.co.uk, is Enduring Love by Ian McEwan, read by Kati Nicholl and Richard E. Grant.

“This week’s free download, brought to you by The Times, Times Online and Audible.co.uk, is Enduring Love by Ian McEwan, read by Kati Nicholl and Richard E. Grant.