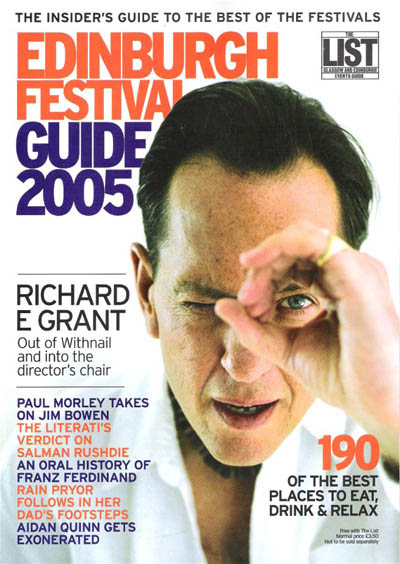

Little Richard

The Daily Mail – Saturday 6th August, 2005

Richard E Grant’s debut as a director is a brave journey into his African childhood, exploring his parents’ alcoholism and adultery. He tells Moira Petty why he had to relive a past in which is father tried to kill him.

A young boy wakes up on the back seat of a car and witnesses a scene that will haunt him forever. His mother reaches over and caresses the driver, his father’s best friend. The 11 year-old knows this is taboo and shuts his eyes when his mother turns to check on him. Thinking he is still asleep, the couple begin a passionate bout of lovemaking while the boy looks on in horror. This extraordinary scene opens Wah-Wah, a powerful film about African colonial life in Swaziland, in the late 1960’s, written and directed by Richard E Grant.

The 48 year-old film star, who was brought up in Swaziland, has talked often of his unhappiness following his mother’s affair and her subsequent divorce from his father. Most observers assumed that Richard had merely drawn on his experiences to create an autobiographical film, which premieres at the Edinburgh International Film Festival later this month.

But, in fact, as Richard now reveals, Wah-Wah is a precise, poignant facsimile of his traumatic childhood, details of which he has not previously divulged. “When I sat down to write it, I had to forget who it might affect. I just wrote as truthfully as I could,” he says.

Despite his leading position in Swazi society, and a second marriage, Richard’s father never recovered from the faithlessness of his first wife. He sank into alcoholism, causing the father-son relationship with Richard to reverse. At one point, when Richard was 15, his father even fired a pistol at his son in a drunken bid to kill him.

There is only one major deviation from the truth in the script. The film portrays the young boy as an only child, but Richard has a brother, Stuart, two and a half years his junior, now an accountant in South Africa. Richard says the omission is because he did not want the focus to waver from his own young self, but he admits there has also always been animosity between the brothers, who have not met since their father’s funeral in 1981.

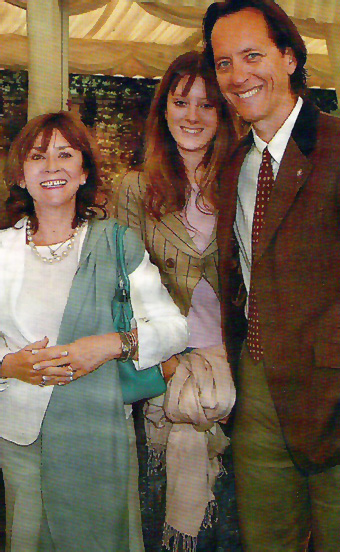

Shot with a delicate cinematography showing the beauty of the African landscape, the film stars Gabriel Byrne and Miranda Richardson as Richard’s parents; Emily Watson as his stepmother and Julie Walters as a family friend who tries to seduce the abandoned husband. There is also a cameo from Richard’s 16 year-old daughter, Olivia, who was born prematurely after Richard and his wife, voice coach Joan Washington, had suffered three miscarriages and the death of a baby girl soon after birth.

Richard, who does not appear in Wah-Wah himself, achieved stardom in 1987 with his depiction of a drunken bohemian in the cult film Withnail & I. It was his freeway to Hollywood and roles in films including How To Get Ahead in Advertising, Dracula, The Player and The Portrait of a Lady. Despite success and the celebrity circles in which he moves (US comedy actor Steve Martin is one of his closest friends), he has maintained an ironic aloofness about Hollywood that he used to waspish effect in his film diaries, With Nails. He also appears in the Argos TV commercials opposite Julia Sawalha, playing an effete and demanding employer. His substantial fee from the ads (he says 15 days pays the equivalent of three months on a film) allowed him the time off to write Wah-Wah, his firm film script, in 1999.

It took him five more years to find investors for a film by a first-time director, to cast it and to achieve the necessary permission from the King of Swaziland to film there. “He is an absolute monarch ad the Swazis prostrate themselves before him. As a white Swazi, I wasn’t required to do that. We met at the palace where he received diplomats. He pointed to the throne next to his, and asked me to sit there and tell him about the film. All the doors opened to us after that.”

The film is set in 1969, just as Swaziland achieved independence from Britain. Richard’s father was so popular that he was asked to stay on in his job as Swaziland’s Director of Education. The film exposes the hypocrisy for the expats who tolerated adultery but not divorce. It also details how Richard became involved in a production of the musical Camelot, to be staged before Princess Margaret at the independence celebrations.

Acting was Richard’s escape route from his troubled childhood, and ultimately provided him with a new life beyond Africa.

Working on Wah-Wah has been cathartic. “People I’d grown up with were concerned that rewriting my past in such an exposing way could turn me into a basket case. They asked, “Are you going to cope?” Although it was painful, it was a profound experience. My intention was never to be vengeful about my past but, through writing about it, to understand it.”

We are in a hotel near his home in Richmond, Surrey. Richard has flown straight in from Canada, where he is making a World War II film. He hair has been cropped for the role and he is deeply tanned, with an African bead necklace at his throat and a watch on each wrist, one set to UK time and one to whichever country he is working in. Previous interviewers have found him mercurial and liable to complain afterwards about the encounter. Today, though, he speaks with candour.

“The key to my story was that moment in the car, when I knew I was seeing something I shouldn’t have seen. I was shocked about the sex, which I heard as much as I saw. I was so innocent and it forced me into carrying a secret that made me feel terrible. It also instigated my face-twisting, an involuntary movement that lasted for a year and which the boy in the film does. Even now, if I get really shocked, I can feel the ghost of the impulse to do that again. Here, I’ll show you”. His face becomes a gargoyle, mouth wide and snarling, features distorted in a rictus of horror.

While Richard remained living with his father, Henrik Abraham Esterhuysen, a third-generation white Swazi, his mother, Leonie Hogan, a South African, ran off with her mining engineer lover and rarely saw her sons again. When her lover signed a contract wow or in Peru, she attempted a reconciliation with Henrik, but Richard, his father’s protector, told him the real reason for her return and she was shown the door. He father died of lung cancer aged 51, when Richard was 24.

Richard’s relationship with his mother remained fraught until six years ago, when he plucked up the courage to demand answers from her and effected a rapprochement that led directly to the making of Wah-Wah. “My daughter was then about the age I was when my mother left home, and seeing how vulnerable Olivia was prompted me to try to deal with my mother in an adult way. I asked my mother if she could bear to write me a letter to explain things from her point of view. I didn’t think she would, but a couple of months later an 18-page letter arrived. In it, I heard the voice of a woman who, at 21, married a colonial civil servant and then had to follow the strict pecking order of this tin pot country. She also revealed her frustration at not being allowed to work.

“It was revelatory for me and a great unburdening for her. It allowed me to tell her, year by year, my version of what had happened. I told her I had seen her with her lover. She was devastated. As in the film, my mother really did send a wreath to my father’s funeral with a card that read, “As ye sow, so shall ye reap”. I hadn’t previously taken on the full impact of it. Once you understand people, you can’t demonise them and I could write the script without being venomous.” Leonie is now 77 and has been married for 27 years to her second husband – not the man for whom she left Richard’s father. “She was very handsome, the Lauren Bacall of Swaziland,” says Richard. His mother is fully supportive of the film, but was aghast to hear of the incident in which Richard was almost killed by his father.

He kept his revolver on a shelf behind his shirts. He had decided to kill my stepmother, who had tried to leave him, but then he found me in the pantry emptying his crate of Scotch bottles down the sink. He was very drunk and said, “I’m going to blow your brains out”, and chased me round the garden. I felt utterly helpless but I goaded him, saying, “Go on, get it over with.” I thought I was going to die. The gun went off and the bullet whistled past my head and then he was full of self-pity and remorse. The next day he couldn’t remember a thing. I knew he was in pain and had never recovered from my mother’s departure.”

Leonie had come to Richard’s bedroom at 6 am on the day she left to break the news that she was going, and was leaving her sons behind. “By that night, my father was slumped, passed out in his chair. He was one man by day and another by night, when the demon drink took over. I began parenting him, which is the wrong way round, but that has helped make me who I am.” In the film, Richard’s father dies of lung cancer which Richard is 15. “My father took nine months to die, but in the film it is truncated to six weeks.”

His father’s real deathbed scene included a moment that has lodged itself in Richard’s memory. “He could hardly speak, but when my stepmother left the room, he tried to tell me something. He took ages to get the words out, which were, “I never stopped loving her.” I asked him if he meant my stepmother but he said, no, my mother. That was the bomb that went off. That was when I understood how and what he was and the reason for his descent into alcoholism.”

Grieving for his father, Richard left South Africa for London in 1982. With only his experience as co-founder of a radical theatre troupe behind him, he launched himself as an actor. Much later, when he became famous, his brother, Stuart, sold his story to a Sunday newspaper. “I was amazed, but we had never got on. My mother said we were like chalk and cheese.” Stuart complained that Richard had turned up at their father’s funeral with orange hair. “I had dyed my hair blond for a role and he thought that was disrespectful. He called ma a pansy in the article because I didn’t play rugby and drink five pints a night. As a boy, I had a string puppet theatre and was involved in a theatre club, which was deemed sexually questionable. The derision stiffened my resolve to be an actor. And I didn’t ever question my sexuality. I knew who I was.”

Richard’s childhood has naturally affected his attitude towards relationships. “I’m a very loyal person and I put a higher value n monogamy because I witnessed the emotional cost of my father’s cuckolding. In the pre-AIDS Seventies, at drama school in Cape Town, everyone was fiercely bonking everyone else, but all the relationships I’ve had have been long-term. Joan and I have been together since 1983 and married since 1986. I was lucky enough to meet someone I am completely compatible with.”

Joan is eight years older than Richard. “I don’t think about the age difference. She’s not an insecure person and I have to listen to her telling me how gorgeous Orlando Bloom, is, after she’s voice-coached him. When I come back from location, there’s a bit of readjustment but we know each other so well: we know which buttons not to press.”

After a string of miscarriages, Joan gave birth in 1986 to a girl, whom they named Tiffany, who was two months premature. Tragically, she died half an hour later. “Dealing with the death of a child is as testing an experience as you can go through. You see your partner as raw and vulnerable as they can be. It would have been hard for us if we hadn’t had Olivia. It’s a cliche, but being a father is the best thing ever.”

He cast Olivia as the first love of his leading character. “I knew she could act because I had seen her in school plays. Directing her was just a continuation of the conversations we have at home. I met my real first love, an expat’s daughter, in the theatre club. It was an immature love and my hormones were going haywire. I just wanted to kiss someone.”

Richard’s wife was also in Swaziland last year for the shoot and was the voice coach for Emily Watson, who plays Richard’s stepmother as an American (she was really South African). She is the figure who gives the film its name, complaining about all this “Wah-Wah”. Richard says, “it’s what they called the coded way in which colonials spoke.”

Richard is played as a young boy by newcomer, Zac Fox and, as a teenager, by Nicholas Hoult, the star of About A Boy. “In the seven months between casting Nicholas and beginning filming, he grew from 5ft 10in to 6ft 3in. Gabriel Byrne was worried it would look odd, but he hadn’t broadened out and had the gawkiness I had as a teenager.”

Richard, a lanky 6ft 2in. says, “I wasn’t a lady-killer. I was so skinny you could count every rib, and I had acne. I still have the scars.”

Richard is used to dealing with divas. While making Gosford Park, he attended a dinner at which he was seated next to Madonna, who barked that she didn’t like the film’s director, Robert Altman. “I said, “Let’s discuss your film career, shall we?” She gave me the eyeball and then quit having a go. She tried to wrong-foot you to see if you will stand up to her and if you do, you pass the litmus test, but if you fall apart that’s the end.”

Richard’s next film project is to adapt his futuristic novel By Design for the screen, but, for now, he and the cast of Wah-Wah are promoting the film at festivals in Edinburgh and Toronto. Wah-Wah may have been built on unhappiness but, he says with a pearly white smile, watching his formative years being brought to life has, paradoxically, been the happiest experience of his professional life.

Wah-Wah premieres at the Edinburgh International Film Festival on August 17. For tickets tel: 0131 623 8030 or visit www.edfilmfest.org.uk

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.

The REG Temple is the official website for actor, author and director Richard E. Grant.